Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

CHAPTER VII.

Глава VII.

A Mad Tea-Party

БЕЗУМНОЕ ЧАЕПИТИЕ

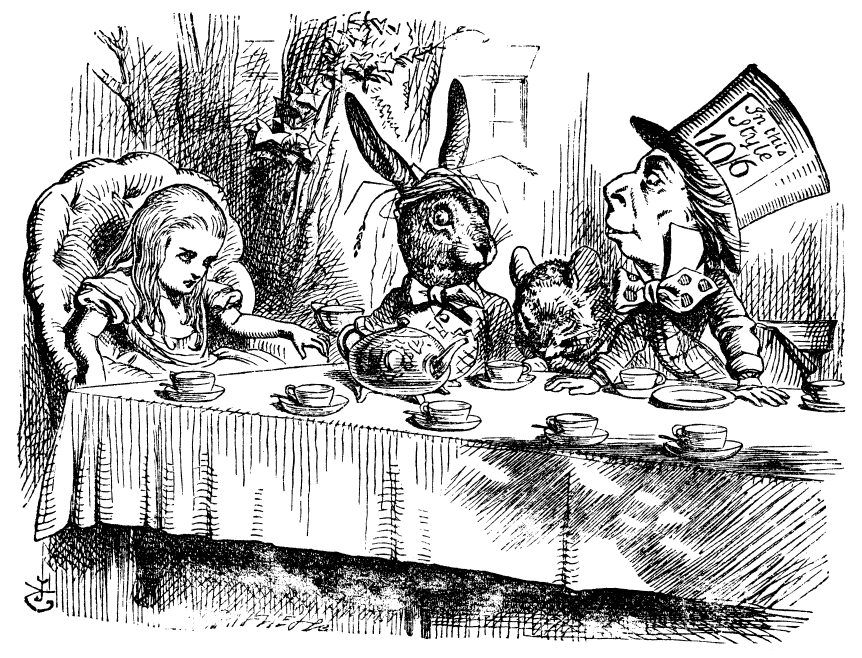

There was a table set out under a tree in front of the house, and the March Hare and the Hatter were having tea at it: a Dormouse was sitting between them, fast asleep, and the other two were using it as a cushion, resting their elbows on it, and talking over its head. 'Very uncomfortable for the Dormouse,' thought Alice; 'only, as it's asleep, I suppose it doesn't mind.'

Около дома под деревом стоял накрытый стол, а за столом пили чай Мартовский Заяц и Болванщик, между ними крепко спала Мышь-Соня. Болванщик и Заяц облокотились на нее, словно на подушку, и разговаривали через ее голову. -- Бедная Соня, -- подумала Алиса. -- Как ей, наверно, неудобно! Впрочем, она спит -- значит, ей все равно.

The table was a large one, but the three were all crowded together at one corner of it: 'No room! No room!' they cried out when they saw Alice coming. 'There's PLENTY of room!' said Alice indignantly, and she sat down in a large arm-chair at one end of the table.

Стол был большой, но чаевники сидели с одного края, на уголке. Завидев Алису, они закричали: -- Занято! Занято! Мест нет! -- Места сколько угодно! -- возмутилась Алиса и уселась в большое кресло во главе стола.

'Have some wine,' the March Hare said in an encouraging tone.

-- Выпей вина, -- бодро предложил Мартовский Заяц.

Alice looked all round the table, but there was nothing on it but tea. 'I don't see any wine,' she remarked.

Алиса посмотрела на стол, но не увидела ни бутылки, ни рюмок. -- Я что-то его не вижу, -- сказала она.

'There isn't any,' said the March Hare.

-- Еще бы! Его здесь нет! --отвечал Мартовский Заяц.

'Then it wasn't very civil of you to offer it,' said Alice angrily.

-- Зачем же вы мне его предлагаете! -- рассердилась Алиса. -- Это не очень-то вежливо.

'It wasn't very civil of you to sit down without being invited,' said the March Hare.

-- А зачем ты уселась без приглашения? -- ответил Мартовский Заяц. -- Это тоже невежливо!

'I didn't know it was YOUR table,' said Alice; 'it's laid for a great many more than three.'

-- Я не знала, что это стол только для вас, -- сказала Алиса. -- Приборов здесь гораздо больше.

'Your hair wants cutting,' said the Hatter. He had been looking at Alice for some time with great curiosity, and this was his first speech.

-- Что-то ты слишком обросла! -- заговорил вдруг Болванщик. До сих пор он молчал и только с любопытством разглядывал Алису. -- Не мешало бы постричься.

'You should learn not to make personal remarks,' Alice said with some severity; 'it's very rude.'

-- Научитесь не переходить на личности, -- отвечала Алиса не без строгости. -- Это очень грубо.

The Hatter opened his eyes very wide on hearing this; but all he SAID was, 'Why is a raven like a writing-desk?'

Болванщик широко открыл глаза, но не нашелся, что ответить. -- Чем ворон похож на конторку? -- спросил он, наконец.

'Come, we shall have some fun now!' thought Alice. 'I'm glad they've begun asking riddles.—I believe I can guess that,' she added aloud.

-- Так-то лучше, -- подумала Алиса. -- Загадки -- это гораздо веселее... -- По-моему, это я могу отгадать, -- сказала она вслух.

'Do you mean that you think you can find out the answer to it?' said the March Hare.

-- Ты хочешь сказать, что думаешь, будто знаешь ответ на эту загадку? -- спросил Мартовский Заяц.

'Exactly so,' said Alice.

-- Совершенно верно, -- согласилась Алиса.

'Then you should say what you mean,' the March Hare went on.

-- Так бы и сказала, -- заметил Мартовский Заяц. -- Нужно всегда говорить то, что думаешь.

'I do,' Alice hastily replied; 'at least—at least I mean what I say—that's the same thing, you know.'

-- Я так и делаю, -- поспешила объяснить Алиса. -- По крайней мере... По крайней мере я всегда думаю то, что говорю... а это одно и то же...

'Not the same thing a bit!' said the Hatter. 'You might just as well say that "I see what I eat" is the same thing as "I eat what I see"!'

-- Совсем не одно и то же, -- возразил Болванщик. -- Так ты еще чего доброго скажешь, будто ``Я вижу то, что ем'' и ``Я ем то, что вижу'', -- одно и то же!

'You might just as well say,' added the March Hare, 'that "I like what I get" is the same thing as "I get what I like"!'

'You might just as well say,' added the Dormouse, who seemed to be talking in his sleep, 'that "I breathe when I sleep" is the same thing as "I sleep when I breathe"!'

-- Так ты еще скажешь, -- проговорила, не открывая глаз, Соня,--будто ``Я дышу, пока сплю'' и ``Я сплю, пока дышу'',--одно и то же!

'It IS the same thing with you,' said the Hatter, and here the conversation dropped, and the party sat silent for a minute, while Alice thought over all she could remember about ravens and writing-desks, which wasn't much.

-- Для тебя-то это, во всяком случае, одно и то же! -- сказал Болванщик, и на этом разговор оборвался. С минуту все сидели молча. Алиса пыталась вспомнить то немногое, что она знала про воронов и конторки.

The Hatter was the first to break the silence. 'What day of the month is it?' he said, turning to Alice: he had taken his watch out of his pocket, and was looking at it uneasily, shaking it every now and then, and holding it to his ear.

Первым заговорил Болвапщик. -- Какое сегодня число? -- спросил он, поворачиваясь к Алисе и вынимая из кармана часы. Он с тревогой поглядел на них, потряс и приложил к уху.

Alice considered a little, and then said 'The fourth.'

Алиса подумала и ответила: -- Четвертое.

'Two days wrong!' sighed the Hatter. 'I told you butter wouldn't suit the works!' he added looking angrily at the March Hare.

-- Отстают на два дня, -- вздохнул Болванщик. -- Я же говорил: нельзя их смазывать сливочным маслом! -- прибавил он сердито, поворачиваясь к Мартовскому Зайцу.

'It was the BEST butter,' the March Hare meekly replied.

-- Масло было самое свежее, -- робко возразил Заяц.

'Yes, but some crumbs must have got in as well,' the Hatter grumbled: 'you shouldn't have put it in with the bread-knife.'

-- Да, ну туда, верно, попали крошки, -- проворчал Болванщик. -- Не надо было мазать хлебным ножом.

The March Hare took the watch and looked at it gloomily: then he dipped it into his cup of tea, and looked at it again: but he could think of nothing better to say than his first remark, 'It was the BEST butter, you know.'

Мартовский Заяц взял часы и уныло посмотрел на них, потом окунул их в чашку с чаем и снова посмотрел. -- Уверяю тебя, масло было самое свежее, -- повторил он. Видно, больше ничего не мог придумать.

Alice had been looking over his shoulder with some curiosity. 'What a funny watch!' she remarked. 'It tells the day of the month, and doesn't tell what o'clock it is!'

Алиса с любопытством выглядывала из-за его плеча. -- Какие смешные часы! -- заметила она. -- Они показывают число, а не час!

'Why should it?' muttered the Hatter. 'Does YOUR watch tell you what year it is?'

-- А что тут такого? -- пробормотал Болванщик. -- Разве твои часы показывают год?

'Of course not,' Alice replied very readily: 'but that's because it stays the same year for such a long time together.'

-- Конечно, нет, -- отвечала с готовностью Алиса. -- Ведь год тянется очень долго!

'Which is just the case with MINE,' said the Hatter.

-- Ну и у меня то же самое! -- сказал Болванщик.

Alice felt dreadfully puzzled. The Hatter's remark seemed to have no sort of meaning in it, and yet it was certainly English. 'I don't quite understand you,' she said, as politely as she could.

Алиса растерялась. В словах Болванщика как будто не было смысла, хоть каждое слово в отдельности и было понятно. -- Я не совсем вас понимаю,--сказала она учтиво.

'The Dormouse is asleep again,' said the Hatter, and he poured a little hot tea upon its nose.

-- Соня опять спит, -- заметил Болванщик и плеснул ей на нос горячего чаю.

The Dormouse shook its head impatiently, and said, without opening its eyes, 'Of course, of course; just what I was going to remark myself.'

Соня с досадой помотала головой и, не открывая глаз, проговорила: -- Конечно, конечно, я как раз собиралась сказать то же самое.

'Have you guessed the riddle yet?' the Hatter said, turning to Alice again.

-- Отгадала загадку? -- спросил Болванщик, снова поворачиваясь к Алисе.

'No, I give it up,' Alice replied: 'what's the answer?'

-- Нет, -- ответила Алиса. -- Сдаюсь. Какой же ответ?

'I haven't the slightest idea,' said the Hatter.

-- Понятия не имею, -- сказал Болванщик.

'Nor I,' said the March Hare.

-- И я тоже, -- подхватил Мартовский Заяц.

Alice sighed wearily. 'I think you might do something better with the time,' she said, 'than waste it in asking riddles that have no answers.'

Алиса вздохнула. -- Если вам нечего делать, -- сказала она с досадой, -- придумали бы что-нибудь получше загадок без ответа. А так только попусту теряете время!

'If you knew Time as well as I do,' said the Hatter, 'you wouldn't talk about wasting IT. It's HIM.'

-- Если бы ты знала Время так же хорошо, как я, -- сказал Болванщик,--ты бы этого не сказала. Его не потеряешь! Не на такого напали!

'I don't know what you mean,' said Alice.

-- Не понимаю,--сказала Алиса.

'Of course you don't!' the Hatter said, tossing his head contemptuously. 'I dare say you never even spoke to Time!'

-- Еще бы! -- презрительно встряхнул головой Болванщик. -- Ты с ним небось никогда и не разговаривала!

'Perhaps not,' Alice cautiously replied: 'but I know I have to beat time when I learn music.'

-- Может, и не разговаривала, -- осторожно отвечала Алиса. -- Зато не раз думала о том, как бы убить время!

'Ah! that accounts for it,' said the Hatter. 'He won't stand beating. Now, if you only kept on good terms with him, he'd do almost anything you liked with the clock. For instance, suppose it were nine o'clock in the morning, just time to begin lessons: you'd only have to whisper a hint to Time, and round goes the clock in a twinkling! Half-past one, time for dinner!'

-- А-а! тогда все понятно, -- сказал Болванщик. -- Убить Время! Разве такое ему может понравиться! Если б ты с ним не ссорилась, могла бы просить у него все, что хочешь. Допустим, сейчас девять часов утра -- пора идти на занятия. А ты шепнула ему словечко и -- р-раз! -- стрелка побежала вперед! Половина второго -- обед!

('I only wish it was,' the March Hare said to itself in a whisper.)

(-- Вот бы хорошо! --тихонько вздохнул Мартовский Заяц).

'That would be grand, certainly,' said Alice thoughtfully: 'but then—I shouldn't be hungry for it, you know.'

-- Конечно, это было бы прекрасно,---задумчиво сказала Алиса, -- но ведь я не успею проголодаться.

'Not at first, perhaps,' said the Hatter: 'but you could keep it to half-past one as long as you liked.'

-- Сначала, возможно, и нет, -- ответил Болванщик. -- Но ведь ты можешь сколько хочешь держать стрелки на половине второго.

'Is that the way YOU manage?' Alice asked.

-- Вы так и поступили, да? -- спросила Алиса.

The Hatter shook his head mournfully. 'Not I!' he replied. 'We quarrelled last March—just before HE went mad, you know—' (pointing with his tea spoon at the March Hare,) '—it was at the great concert given by the Queen of Hearts, and I had to sing

Болванщик мрачно покачал головой. -- Нет, -- ответил он. -- Мы с ним поссорились в марте -- как раз перед тем, как этот вот (он показал ложечкой на Мартовского Зайца) спятил. Королева давала большой концерт, и я должен был петь ``Филина''. Знаешь ты эту песню?

"Twinkle, twinkle, little bat!

How I wonder what you're at!"

Ты мигаешь, филин мой!

Я не знаю, что с тобой.

You know the song, perhaps?'

'I've heard something like it,' said Alice.

--Что-то такое я слышала,--сказала Алиса.

'It goes on, you know,' the Hatter continued, 'in this way:—

-- А дальше вот как, - продолжал Болванщик.

"Up above the world you fly,

Like a tea-tray in the sky.

Twinkle, twinkle—"'

Высоко же ты над нами,

Как поднос под небесами!

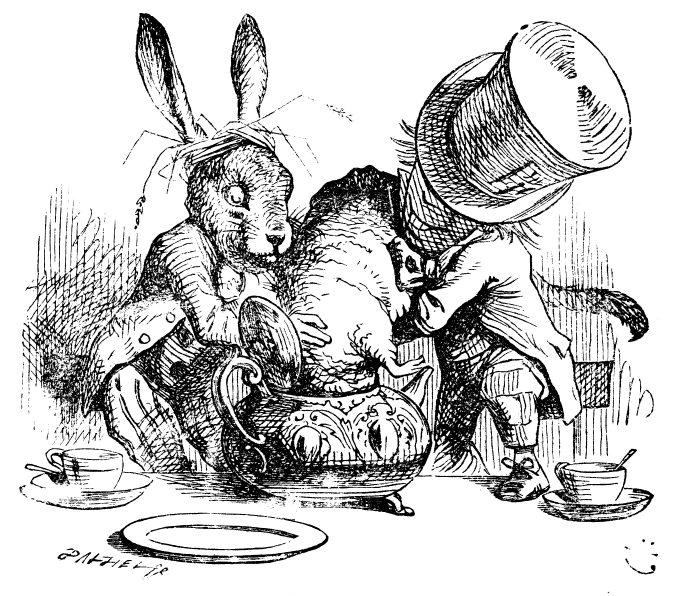

Here the Dormouse shook itself, and began singing in its sleep 'Twinkle, twinkle, twinkle, twinkle—' and went on so long that they had to pinch it to make it stop.

Тут Соня встрепенулась и запела во сне: ``Ты мигаешь, мигаешь, мигаешь...'' Она никак не могла остановиться. Пришлось Зайцу и Болванщику ущипнуть ее с двух сторон, чтобы она замолчала.

'Well, I'd hardly finished the first verse,' said the Hatter, 'when the Queen jumped up and bawled out, "He's murdering the time! Off with his head!"'

-- Только я кончил первый куплет, как кто-то сказал: ``Конечно лучше б он помолчал, но надо же как-то убить время!'' Королева как закричит: ``Убить Время! Он хочет убить Время! Рубите ему голову!''

'How dreadfully savage!' exclaimed Alice.

-- Какая жестокость! -- воскликнула Алиса.

'And ever since that,' the Hatter went on in a mournful tone, 'he won't do a thing I ask! It's always six o'clock now.'

-- С тех пор, -- продолжал грустно Болванщик, -- Время для меня палец о палец не ударит! И на часах все шесть...

A bright idea came into Alice's head. 'Is that the reason so many tea-things are put out here?' she asked.

Тут Алису осенило. -- Поэтому здесь и накрыто к чаю? --- спросила она.

'Yes, that's it,' said the Hatter with a sigh: 'it's always tea-time, and we've no time to wash the things between whiles.'

-- Да,--отвечал Болванщик со вздохом.--Здесь всегда пора пить чай. Мы не успеваем даже посуду вымыть!

'Then you keep moving round, I suppose?' said Alice.

-- И просто пересаживаетесь, да? -- догадалась Алиса.

'Exactly so,' said the Hatter: 'as the things get used up.'

-- Совершенно верно, -- сказал Болванщик. -- Выпьем чашку и пересядем к следующей.

'But what happens when you come to the beginning again?' Alice ventured to ask.

-- А когда дойдете до конца, тогда что? -- рискнула спросить Алиса.

'Suppose we change the subject,' the March Hare interrupted, yawning. 'I'm getting tired of this. I vote the young lady tells us a story.'

-- А что, если мы переменим тему?--спросил Мартовский Заяц и широко зевнул. -- Надоели мне эти разговоры. Я предлагаю: пусть барышня расскажет нам сказку.

'I'm afraid I don't know one,' said Alice, rather alarmed at the proposal.

-- Боюсь, что я ничего не знаю, -- испугалась Алиса.

'Then the Dormouse shall!' they both cried. 'Wake up, Dormouse!' And they pinched it on both sides at once.

-- Тогда пусть рассказывает Соня, -- закричали Болванщик и Заяц. -- Соня, проснись!

The Dormouse slowly opened his eyes. 'I wasn't asleep,' he said in a hoarse, feeble voice: 'I heard every word you fellows were saying.'

Сопя медленно открыла глаза. --Я и не думала спать, -- прошептала она хрипло. -- Я слышала все, что вы говорили.

'Tell us a story!' said the March Hare.

-- Рассказывай сказку! -- потребовал Мартовский Заяц.

'Yes, please do!' pleaded Alice.

-- Да, пожалуйста, расскажите,--подхватила Алиса.

'And be quick about it,' added the Hatter, 'or you'll be asleep again before it's done.'

-- И поторапливайся, -- прибавил Болванщик. --А то опять заснешь!

'Once upon a time there were three little sisters,' the Dormouse began in a great hurry; 'and their names were Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie; and they lived at the bottom of a well—'

-- Жили-были три сестрички, -- быстро начала Соня. -- Звали их Элен, Лэси и Тилли, а жили они на дне колодца...

'What did they live on?' said Alice, who always took a great interest in questions of eating and drinking.

-- А что они ели?--спросила Алиса. Ее всегда интересовало, что люди едят и пьют.

'They lived on treacle,' said the Dormouse, after thinking a minute or two.

-- Кисель,--отвечала, немного подумав, Соня.

'They couldn't have done that, you know,' Alice gently remarked; 'they'd have been ill.'

-- Все время один кисель? Это невозможно, -- мягко возразила Алиса. -- Они бы тогда заболели.

'So they were,' said the Dormouse; 'VERY ill.'

-- Они и заболели, -- сказала Соня. -- И очень серьезно.

Alice tried to fancy to herself what such an extraordinary ways of living would be like, but it puzzled her too much, so she went on: 'But why did they live at the bottom of a well?'

Алиса пыталась понять, как это можно всю жизнь есть один кисель, но это было так странно и удивительно, что она только спросила: -- А почему они жили на дне колодца?

'Take some more tea,' the March Hare said to Alice, very earnestly.

-- Выпей еще чаю, -- сказал Мартовский Заяц, наклоняясь к Алисе.

'I've had nothing yet,' Alice replied in an offended tone, 'so I can't take more.'

-- Еще? -- переспросила Алиса с обидой. -- Я пока ничего не пила.

-- Больше чаю она не желает, -- произнес Мартовский Заяц в пространство.

'You mean you can't take LESS,' said the Hatter: 'it's very easy to take MORE than nothing.'

-- Ты, верно, хочешь сказать, что меньше чаю она не желает: гораздо легче выпить больше, а не меньше, чем ничего, -- сказал Болванщик.

'Nobody asked YOUR opinion,' said Alice.

-- Вашего мнения никто не спрашивал, -- сказала Алиса.

'Who's making personal remarks now?' the Hatter asked triumphantly.

-- А теперь кто переходит на личности? -- спросил Болванщик с торжеством.

Alice did not quite know what to say to this: so she helped herself to some tea and bread-and-butter, and then turned to the Dormouse, and repeated her question. 'Why did they live at the bottom of a well?'

Алиса не знала, что на это ответить. Она налила себе чаю и намазала хлеб маслом, а потом повернулась к Соне и повторила свой вопрос: -- Так почему же они жили на дне колодца?

The Dormouse again took a minute or two to think about it, and then said, 'It was a treacle-well.'

Соня опять задумалась и, наконец, сказала: -- Потому что в колодце был кисель.

'There's no such thing!' Alice was beginning very angrily, but the Hatter and the March Hare went 'Sh! sh!' and the Dormouse sulkily remarked, 'If you can't be civil, you'd better finish the story for yourself.'

-- Таких колодцев не бывает,--возмущенно закричала Алиса. Но Болванщик и Мартовский Заяц на нее зашикали, а Соня угрюмо пробормотала: -- Если ты не умеешь себя вести, досказывай сама!

'No, please go on!' Alice said very humbly; 'I won't interrupt again. I dare say there may be ONE.'

-- Простите, -- покорно сказала Алиса. -- Пожалуйста, продолжайте, я больше не буду перебивать. Может, где-нибудь и есть один такой колодец.

'One, indeed!' said the Dormouse indignantly. However, he consented to go on. 'And so these three little sisters—they were learning to draw, you know—'

-- Тоже сказала -- ``один''! -- фыркнула Соня. Впрочем, она согласилась продолжать рассказ. -- И надо вам сказать, что эти три сестрички жили припиваючи...

'What did they draw?' said Alice, quite forgetting her promise.

-- Припеваючи?--переспросила Алиса.--А что они пели?

'Treacle,' said the Dormouse, without considering at all this time.

-- Не пели, а пили -- ответила Соня. -- Кисель, конечно.

'I want a clean cup,' interrupted the Hatter: 'let's all move one place on.'

-- Мне нужна чистая чашка,--перебил ее Болванщик.--Давайте подвинемся.

He moved on as he spoke, and the Dormouse followed him: the March Hare moved into the Dormouse's place, and Alice rather unwillingly took the place of the March Hare. The Hatter was the only one who got any advantage from the change: and Alice was a good deal worse off than before, as the March Hare had just upset the milk-jug into his plate.

И он пересел на соседний стул. Соня села на его место. Мартовский Заяц--на место Сони, а Алиса, скрепя сердцем,--на место Зайца. Выиграл при этом один Болванщик; Алиса, напротив, сильно проиграла, потому что Мартовский Заяц только что опрокинул себе в тарелку молочник.

Alice did not wish to offend the Dormouse again, so she began very cautiously: 'But I don't understand. Where did they draw the treacle from?'

Алисе не хотелось опять обижать Соню, и она осторожно спросила: -- Я не понимаю... Как же они там жили?

'You can draw water out of a water-well,' said the Hatter; 'so I should think you could draw treacle out of a treacle-well—eh, stupid?'

-- Чего там не понимать, -- сказал Болванщик. -- Живут же рыбы в воде. А эти сестрички жили в киселе! Поняла, глупышка?

'But they were IN the well,' Alice said to the Dormouse, not choosing to notice this last remark.

-- Но почему? -- спросила Алиса Соню, сделав вид, что не слышала последнего замечания Болванщика.

'Of course they were', said the Dormouse; '—well in.'

-- Потому что они были кисельные барышни.

This answer so confused poor Alice, that she let the Dormouse go on for some time without interrupting it.

Этот ответ так смутил бедную Алису, что она замолчала.

'They were learning to draw,' the Dormouse went on, yawning and rubbing its eyes, for it was getting very sleepy; 'and they drew all manner of things—everything that begins with an M—'

-- Так они и жили,-- продолжала Соня сонным голосом, зевая и протирая глаза, -- как рыбы в киселе. А еще они рисовали... всякую всячину... все, что начинается на М.

'Why with an M?' said Alice.

-- Почему на М? -- спросила Алиса.

'Why not?' said the March Hare.

-- А почему бы и нет? -- спросил Мартовский Заяц.

Alice was silent.

Алиса промолчала.

The Dormouse had closed its eyes by this time, and was going off into a doze; but, on being pinched by the Hatter, it woke up again with a little shriek, and went on: '—that begins with an M, such as mouse-traps, and the moon, and memory, and muchness—you know you say things are "much of a muchness"—did you ever see such a thing as a drawing of a muchness?'

-- Мне бы тоже хотелось порисовать, -- сказала она, наконец. -- У колодца. -- Порисовать и уколоться? -- переспросил Заяц. Соня меж тем закрыла глаза и задремала. Но тут Болванщик ее ущипнул, она взвизгнула и проснулась. -- ...начинается на М,--продолжала она.--Они рисовали мышеловки, месяц, математику, множество... Ты когда-нибудь видела, как рисуют множество? -- Множество чего? -- спросила Алиса. -- Ничего, -- отвечала Соня. -- Просто множество!

'Really, now you ask me,' said Alice, very much confused, 'I don't think—'

-- Не знаю, -- начала Алиса, -- может...

'Then you shouldn't talk,' said the Hatter.

-- А не знаешь -- молчи, -- оборвал ее Болванщик.

This piece of rudeness was more than Alice could bear: she got up in great disgust, and walked off; the Dormouse fell asleep instantly, and neither of the others took the least notice of her going, though she looked back once or twice, half hoping that they would call after her: the last time she saw them, they were trying to put the Dormouse into the teapot.

Такой грубости Алиса стерпеть не могла: она молча встала и пошла прочь. Соня тут же заснула, а Заяц и Болванщик не обратили на Алисин уход никакого внимания, хоть она и обернулась раза два, надеясь, что они одумаются и позовут ее обратно. Оглянувшись в последний раз, она увидела, что они засовывают Соню в чайник.

'At any rate I'll never go THERE again!' said Alice as she picked her way through the wood. 'It's the stupidest tea-party I ever was at in all my life!'

-- Больше я туда ни за что не пойду! --твердила про себя Алиса, пробираясь по лесу. -- В жизни не видела такого глупого чаепития!

Just as she said this, she noticed that one of the trees had a door leading right into it. 'That's very curious!' she thought. 'But everything's curious today. I think I may as well go in at once.' And in she went.

Тут она заметила в одном дереве дверцу. -- Как странно! -- подумала Алиса. -- Впрочем, сегодня все странно. Войду-ка я в эту дверцу. Так она и сделала.

Once more she found herself in the long hall, and close to the little glass table. 'Now, I'll manage better this time,' she said to herself, and began by taking the little golden key, and unlocking the door that led into the garden. Then she went to work nibbling at the mushroom (she had kept a piece of it in her pocket) till she was about a foot high: then she walked down the little passage: and THEN—she found herself at last in the beautiful garden, among the bright flower-beds and the cool fountains.

И снова она оказалась в длинном зале возле стеклянного столика. -- Ну теперь-то я буду умнее,--сказала она про себя, взяла ключик и прежде всего отперла дверцу, ведущую в сад, А потом вынула кусочки гриба, которые лежали у нее в кармане, и ела, пока не стала с фут ростом. Тогда она пробралась по узкому коридорчику и наконец--очутилась в чудесном саду среди ярких цветов и прохладных фонтанов.

Audio from LibreVox.org